Nuance? In this Economy??

Selective recession hits Art Basel, while Paul Pfeiffer's epic survey departs from LA

Written to be read on your phone.

Where spring and fall used to be blockbuster seasons, and summer was for phoned-in group shows, art in LA is so GOOD right now—the smartest, most exciting stuff we’ve seen after a boring stretch of quiet luxury. There’s Gretchen Bender and Otto Piene at Spruth Magers; Devin Troy Strother’s performance at Sow & Tailor; the multi-sensory Wilt at Canary Test; and Matthew Barney at Regen Projects. I’m also psyched to see Chiffon Thomas at Kohn, Mickalene at The Broad and Josh Kline at MOCA Grand.

Today I asked a few friends if they wanted to see a Cremaster Cycle screening and only gay men said yes; full report on our collective review later.

PAUL PFEIFFER’S TENDERNESS AND VIRALITY

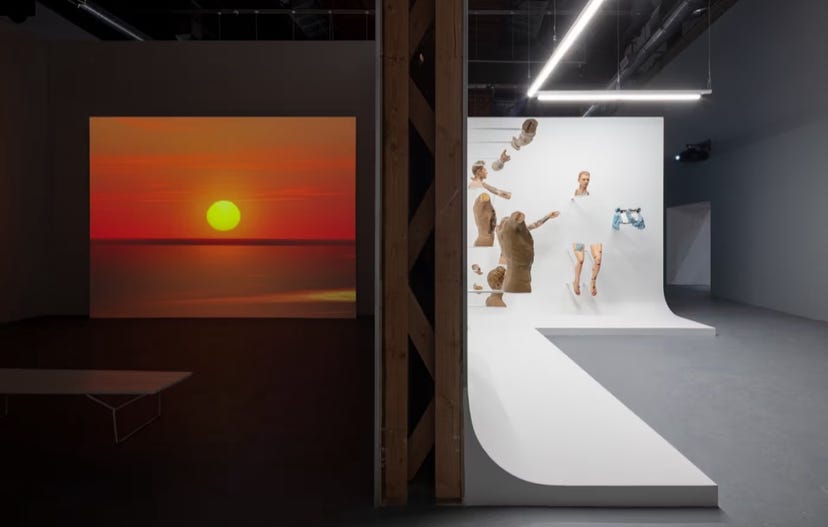

For now, let’s wave a fond farewell to Paul Pfeiffer’s 25-ish-year survey at MOCA Geffen during its closing weekend, and give a round of applause for its conceptual and formal prescience; his close reads of early 2000s popular entertainment unknowingly defined the social media dynamics we’re living out today. In Fragment of a Crucifixion (After Francis Bacon), 1999, the victorious, guttural roar of an NBA player plays and rewinds in an endless swinging loop—what today we call a Boomerang in social media parlance—on a tiny projection that pulls you in close, creating the physical and emotional intimacy we now enjoy with our phones.

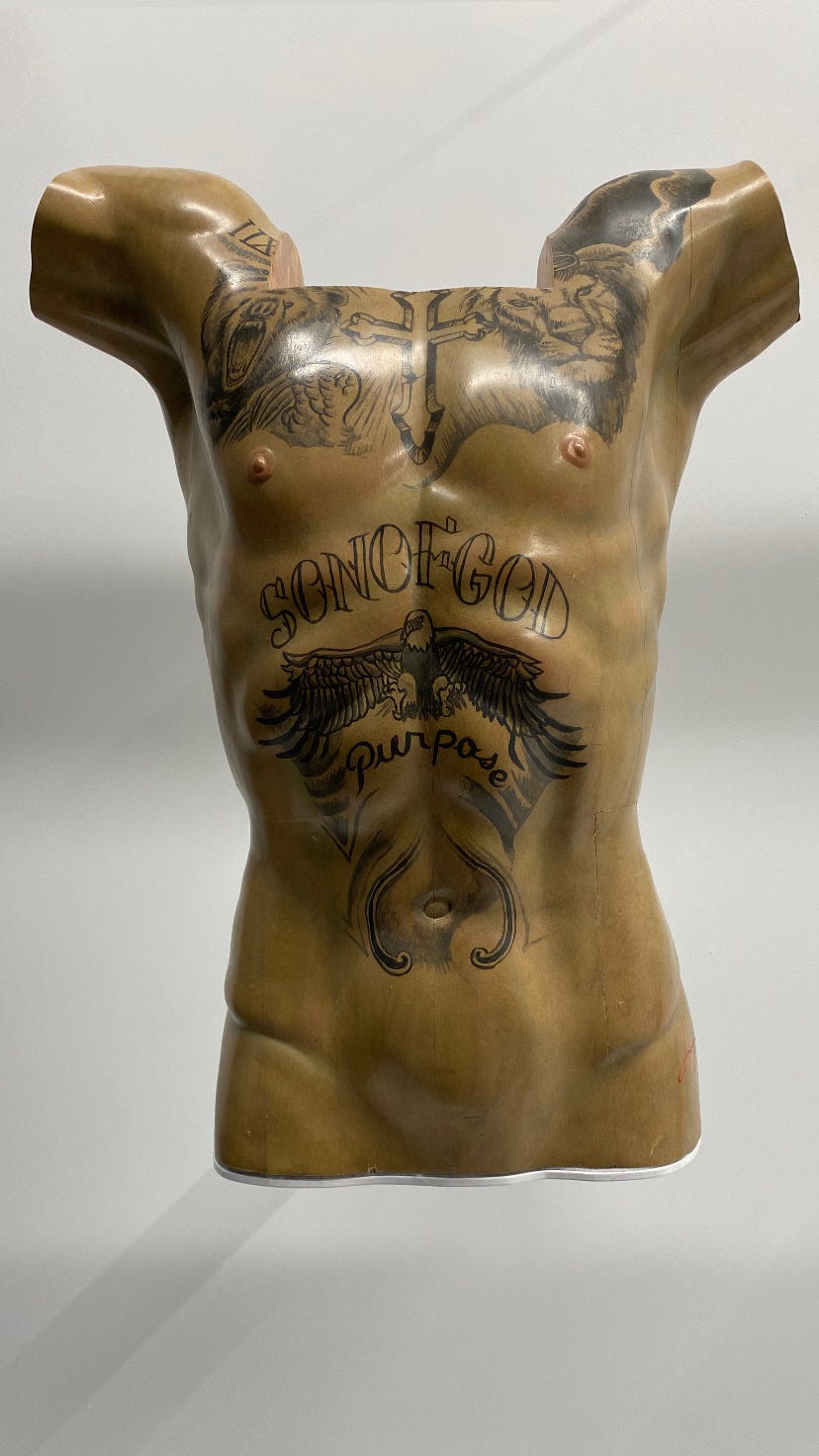

I don’t know anyone who didn’t fall in love with this show, which at its heart is about the mediation of beauty, seduction, and worship. Deconstructing these phenomena in pop culture, Pfeiffer found strange truths or surprising connections between beloved and unlike things, including the quasi-religious behavior of fandom and celebrity worship. His Incarnator sculptures seamlessly merge two objects of adulation—Justin Bieber and Jesus Christ—in the same body, superimposing the pop star’s tattoos on the sinewy torso of the son of the cross. In this new context, I see something I missed after an entire childhood of attending mass: in catholic iconography, Jesus is always hot???

Incarnator was fabricated by Filipino encarnadores sculptors, whose specialty is carving and painting wood into flesh so lifelike, it inspires the weeping and adoration of the devout. What they and Pfeiffer similarly embrace is the original, spiritual function of art; for the artist to infuse a living, emotional resonance in their work, and for the viewer to look upon it and feel deeply moved. That same tenderness and sensitivity equally applies to his video works, as in the aforementioned NBA/Bacon boomerang. Using the era’s nascent digital technologies, Pfeiffer manually isolated the emotional climax of the event and invented a way of prolonging and amplifying it, unlocking the mechanics of virality, or perhaps something deeper—the profound science through which imagery captivates us.

One of my fav works is not about emotional climax but actually its inverse, a spectacular kind of edging. The large-scale video Morning after the Deluge, 2001, is just you staring at the sun, suspended in a fixed position between sunset and sunrise; the horizon is moving, but as you behold this great beauty, it seems the world is standing still.

NUANCE? IN THIS ECONOMY?

What if we met in the Agnes Denes field and took a selfie under the Art Basel logo?

I sadly didn’t make it to Basel this year, but the state of the fair seemed to unfold across The Art Newspaper headlines in order of rapidly descending optimism:

Blue-chip galleries report steady stream of eight-figure deals on Art Basel's second day

Big ticket sales at Art Basel mask a nuanced market moment

Tepid sales at Liste underscore a soft market for smaller galleries

Dominique Lévy is the one who described the moment as “nuanced”—“What’s happening in the art market is hard to describe, very hard to decipher,” she said. But I say, hey, let’s give it a try.

The top tier reported that things are fine: Iwan Wirth, whose reported sales included a $16 million Arshile and a $13.5 million Georgia O’Keefe, put out a statement shrugging off art-market “doom porn,” and TAN echoed the mega-gallerist’s sentiments. The paper cited the art world’s “friction between facts and feelings” that reportedly mirrors the mood of the greater economy. There, despite “positive data-based indicators”—“rising real incomes, relatively low unemployment, narrowing inequality, significantly eased (if still stubborn) inflation and more”—the public maintains its negative economic outlook. Mainstream news for the last year or two has described this phenomenon as the “vibecession,” diligently waiting for the inexplicable nay-saying to pass.

Why Are People So Down About the Economy? Theories Abound.

Is the U.S. in a "vibecession"? Here's why Americans are gloomy even as the economy improves.

“Vibecession”? - The paradox between hard data and sentiment

Dealers at Liste, however, painted a different picture, reporting a swath of unsold sculpture and installation, with “tepid sales” of wall-based works going for around $5,500 and below. Artnet also noted Liste’s marked transition into “safe” work, and a number of failed auction sales resurfacing at Art Basel. Concurrent headlines outside of Basel meanwhile included the cancellation of New York’s Photofairs “until market conditions improve”; rounds of layoffs at the auction houses; and a growing list of gallery closures. In my educated guess, it seems that except for those in the position to buy and sell multi-million-dollar works, the art world’s worries are completely valid. The insistence that everything is fine actually seems to underscore a state of masked panic and denial.

“Vibecession” offers a mantra of magical thinking; especially given the stakes of the next US election, we all want the market to succeed. But reality more likely aligns with “selective recession,” a phrase I’ve seen only recently from JP Morgan retail analyst Matthew Boss. In the face of the economy’s highest earners amassing $40 trillion in net worth since 2019, he said that lower- and middle-income consumers are feeling significant pressure: “You have the consumer at the high end who is being more choiceful. The low-end I do think is a melting ice cube... [B]y our survey, over 70% of low-income consumers right now are saying that they're struggling to make ends meet.” The bureau of labor statistics also states that consumer prices overall are 22% higher than they were in 2019. in 2022, UBS economist Paul Donovan was already talking about how although the ultra-wealthy remain largely insulated, increases in food and fuel costs are “disproportionately significant for lower income groups.” An example of selective recession in the art world: the opening of a new big-box David Zwirner location in LA just as David Lewis shuttered.

Sidenote: David Zwirner actually does have a phoned-in group show right now. (He’s said to have personally chosen the works, but my question is, from what?)

In Wirth’s statement, he celebrated the market’s return to “a more humane pace,” where “the most discerning international collectors are committing here and now to the very best of the best.” I agree that this is a good thing: the buying frenzy of the early pandemic supported the proliferation of really terrible art, and according to various dealers and advisors, collectors now have to live with their regrettable purchases. But! So many smaller dealers expanded their enterprises to match the speed and scale of a bubble that is now rapidly shrinking, having opened second and third locations in the same city (in LA: Nonaka-Hill, Ghebaly, M+B among them). New “for lease” signs on these secondary storefronts suggest a quiet shrinking, while the perceived obligation to keep doing fairs despite their declining ROI also seems particularly cruel. The market correction is here, and it’s really going to hurt.

One last note: an Art Basel director once told me that if dealers tell you they’re doing fine but they’ve heard their peers are not, it means they’re also not doing fine.